by Grete Simkuté

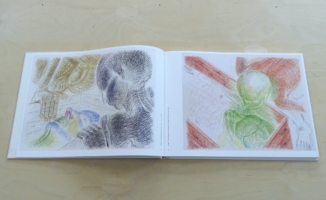

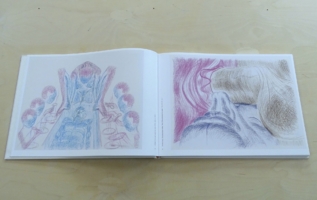

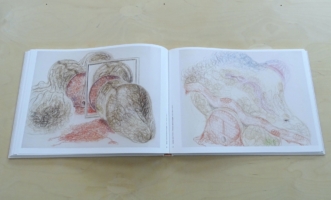

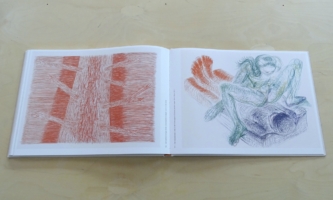

A female figure crouches wide-legged on top of a chest, her genitalia spread over a lifeless male head. She urinates. Consumed by her animalism, she appears unconcerned by the presence of the six undefined figures, whom in turn complete the scene. Further, even, they are enjoying a meal. Gratuitous and unperturbed, they bring the spoons to their mouths, blow softly to cool their food, and warm themselves on the steamy, rising vapor. What are we looking at here? The image simultaneously promotes intrigue and annoyance; despite the confusion it creates, it feels also strangely familiar. Just like the parallel worlds found in poetry or a nightly dream, it appears that part of ourselves can be convinced by the illogical. For those who slip into the inner reservoir of references and symbols the visual riddle is promised.

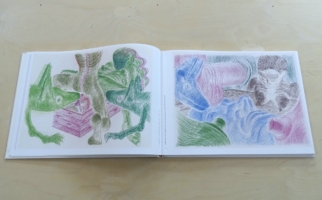

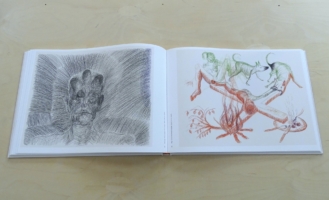

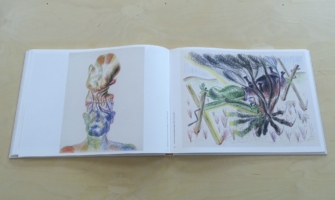

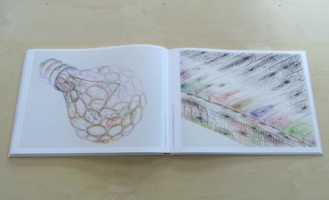

The oeuvre of Pieter Slagboom has been described more than once as “the best kept secret”. A striking description, it encompasses the multilevel, ambiguous space between thematic extremes. Civilization versus instinct, death versus life, nourishment versus excrement, man versus woman, worship versus disdain, they co-exist in Slagboom’s drawings, flowing into one another and creating new, interpretive frameworks. As a ceaseless point of tension between cultural, social, and biological forces, Slagboom’s protagonist, man, is a torn creature. He is ever in conflict, ever seeking, never finding. In particular, the friction between physicality and religion fascinates the artist, revealing the true purity of the first and compelling absurdity of the second. Slagboom looks with a certain self-reflexivity at the meanings that we, as society, give to bodily expressions (excrement, sex, death), calling into question their apparent immutability.

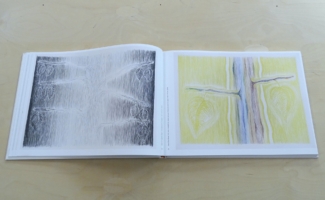

Is life, including everyday reality, really happening to us, or does it present the opportunity to look further? Slagboom is principally an image relativist; he views the world around him with a detached gaze (as far as possible, wherever he is aware), continuously disconnecting visual representation from the most obvious meaning. In shuffling them together, he creates images which are, in turn, completely autonomous. Because they do not originate from only a single story (such as an illustration), but rather, originate from an abstract question, the drawings maintain a suggested rather than prescriptive function. They steer but do not control, simultaneously complex and clear. As seen in the best works emerging from the absurdist tradition, they awaken a multitude of emotions (should you now be crying or laughing? Is this pure seriousness or one big joke?) and therefore confront us with our own perplexity.

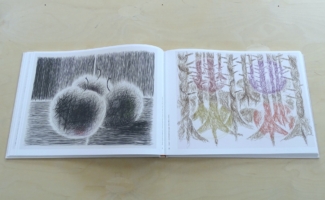

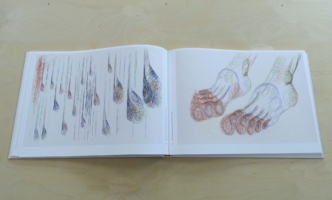

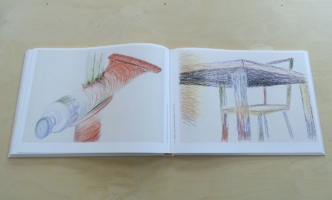

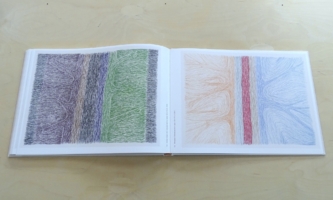

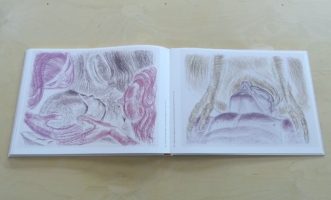

By creating drawings which are difficult to look at, in which the viewer instinctively wants to turn away, Slagboom aims for a certain image resistance. He attempts to achieve this not only in a thematic, but also in a formal sense. This therefore brings him a subtle yet very definitive separation between the world of the subject and the world of color. The scene in which the female figure empties her bladder on an (apparently) lifeless body is depicted in soft blue and pink tones (interesting to note here is that the color blue is used to depict both the dead body as well as the living, the latter of which to a lesser extent also emits a sparkling glow. It is almost as if Slagboom suggests that death already exists in us, the living. Or, in the words of the Belgian drama author Maurice Maeterlinck, “The living are the dead on holiday”. The brightness and almost sweet charm of the colors as well as the tenderness that is visible in the pencil lines contrasts with the often explicit scenes they form. In this sense, the color does not encourage a benevolent attitude towards the subject, but rather, casts it in doubt and causes its rupture. Just as vibrant colors in nature do not uncommonly indicate poison for humans, so do Slagboom’s color choices (in part) poison the subject. “ It’s the confusion [of the compressed, contradictory themes, GS] which create space in which the world of color is inserted,” said the artist. It is the color which detaches the topic from the possible cliché meanings while at the same time complicating the image and opening it to a multitude of interpretations.

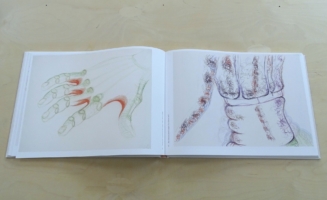

The fracture of the (modern) human being is largely addressed, as previously stated, in Slagboom’s work in the contrast between biology and culture (in which he also takes religion into account). The artist seems to want to emphasize the tension found in the two tempos in which humanity now lives. On the one hand there is the body and its instincts, which have hardly changed in the past millennia, while on the other there is civilization, which has organized rapidly in hundreds nation states managed by complex governments and other systems of technology-driven power. Slagboom emphasizes the most basic, elementary aspects that have proven to be almost unchangeable, the ones which make man human. He does not propagate a body cult, but rather, tries to coax the bodily functions, which in many prevailing views of society seem to be ‘curbed’, out of its penitentiary corner. It is not rare that Slagboom zooms in on the corporeal body, fixating with precision on the smallest blood vessels, hairs, and the icy transparency of the skin. With respect to this the human body quickly takes on architectural, spatial properties, getting back the power forfeited to the lost, searching man.

Slagboom’s visual style and technical signature are extremely individualistic and recognizable. His practice is primarily an intellectual activity, as his drawings appear to be related to sub consciousness, and are created (as much) by carefully observing and analyzing his own personality, immediate environment, and the world around him. Slagboom draws parallels and translates them through the use of rich imagery, and ratio and intuition go within his practice hand in hand.

by Nickel van Duijvenboden:

Little dialectic of a city wanderer

It’s bad taste to compose something like that. I composed it. Do you know why? It’s part of the dialectic of the artist.

– Hanns Eisler[1]

Only once did I end up in another part of the world without wanting to, orphaned and unprepared. In a matter of hours, I was plunged into a wholly unfamiliar culture. I did try to take in at least some of my surroundings, but getting there had drained me so utterly that I still went into the streets ‘cold’. I couldn’t find my bearings and didn’t venture further than the block around the hotel. Out of impotence, I took some pictures of the side of the road with a group of passersby. There were three women draped in bright colours engaged in a conversation, and as I framed them, I heard them shouting something at me. I quickly retreated. It was not until I reviewed my pictures that I saw their irked expressions. I couldn’t just step out and capture their world; it was absurd to even try.

I paced around the parking lot in front of the hotel to kill some time. When a taxi van finally arrived, I got in together with my family. We drove a few blocks until we came to a busy roundabout, where we entered an unpaved driveway covertly wedged between two exits. The area was edged by trees and teeming with people. Almost everyone in sight was weeping and clutching someone else, gathering into throngs that spiraled around coffins teetering in and out of balance, held over their heads by strong arms.

The city mortuary comprised a squat, brick structure; all doors were wide open, with people swarming in and out. A wiry man in a suit greeted us and proceeded to one of the doors at the back of the building. Even before entering, the stench was stifling – we couldn’t even inhale enough to cry. Inside, several men loitered in the dark corners – I didn’t know why. Wide-eyed, they observed as we reluctantly approached the table in the middle. Underneath a piece of cotton dotted with dark stains, I could make out the outlines of a body.

‘You said you would dress and prepare him!’ my mother said to the man in the suit.

‘Yes,’ he mumbled. He pinched the corners of the cloth and unfolded. The cotton wrinkled on the bare chest.

It was hard not to shrink back. Had I been the child of the person lying there? All of a sudden, I’d lost that certainty. On the one hand, I simply wanted to whimper; on the other, I felt a surge of indignation about the inescapable barrenness of the situation, an affront to any longing for ritual.

Georges Bataille situates the birth of man around the time that they, unlike animals, first recoiled from a dead body in their midst – the awareness that this is neither a person nor an object, but something in between – consequently inventing rituals to treat their dead.

‘Shoo!’ I hissed at the men who hadn’t stopped eyeing us, waving them away as though they were flies. But my fury only seemed to make our spectacle more beguiling. Again I focused on the stony face that I knew so intimately, but I still felt naked to their cruel curiosity. It had become clear to me that reality just went on, despite something else having had ceased. An intimacy, a sanctuary, had reached its final limit.

And the gazes whispered: what are you doing here?

Rote Insel, Berlin, September 2017

Dear Pieter,

Some time ago you wondered what it must be like if I “emptied my head”.[2] Unsurprisingly, I still owe you an answer. It’s a fair question, its implied challenge no less deserved. As one who summons an inner world in drawings, you probably know better than I that the head doesn’t allow emptying; it’s as pointless as waiting for the ability to perceive your surroundings without any distortions or private thoughts – without histories and unconscious layers enmeshing what is present.

There are multiple versions of the present, which address multiple layers of consciousness. I appreciated that afresh as I took a stroll through the neighbourhood just now, as a means of exploration and also to avoid the bare interior of my new writing room. Every exploration, even a mental one, presupposes a topography. The situationist drifters had an excellent term for it: ‘psychogeography’. Walter Benjamin, remembering the streets, bridges and parks of his childhood in his Berlin Chronicle (1932), notes that ‘for a long time […] I have toyed with the idea of dividing up the spaces of life – bios – cartographically.’[3] At first, he imagined the kind of map in which buildings are coloured in; later, he would be ‘more inclined to look to an ordnance map, should any exist of city interiors. But probably none do, since we misconceive theaters of war.’

In any case, no matter how curious and fresh my observations are, I can’t separate the breadth and tranquility of this ‘Red Island’ – so named because of a long past socialist uprising, and because it’s wedged between the many railway lines that once extended south from the Gleisdreieck, its rusty-red tracks still protruding from the undergrowth at odd places – from the thoughts I’ve hauled here with me.

I know you love to wander through this city, and that it has inspired some of your drawings. Several of them, you told me, even started out as a sketch in the street. This surprises me on the one hand, because there’s no obvious correspondence between the feverishly internal visual language in your work and the city drift as both a phenomenon and a phenomenology. On the other hand, for reasons mentioned above, walking gives rise to a certain dialectic, a thought-current running in the opposite direction, seemingly averting itself from what is ready-at-hand, turning it inside out.

The dialectic demands that I suspend my blissful sense of safety and anonymity in favour of more haunted and uncanny thoughts. Here, for example, I sense a continuous proximity of times and worlds that are far away from my own, a depth and weight that have something to do with those overgrown and half-sunken railroad tracks, and which press like a heavy load-bearing body (Speer’s Schwerbelastungskörper is just around the corner[4]) on the foothold of the present as if from below.

It seems obvious to locate this ever-present heaviness in a past that has been extensively archived and described, and has therefore acquired the grip of a system of roots. I know that somewhere deep down I relate to those roots, and that the possession of this grip is something familiar. The phenomenon of ‘guilty landscape’ perhaps epitomises this. We look at a tree and wonder what it may have witnessed; we peel it off, as it were, layer by layer, until we arrive at the young shoot. I suppose this perspective, which ascribes a collective meaning to objects and landscapes, is culturally determined. Yet no matter how heavy minded the gaze, this way of looking paradoxically harbours a certain innocence, in that one’s perception is always governed by the knowledge and freedom of the present time and the stability that makes such reflections possible, making the facts appear absurd, grotesque.

‘There where that slide is,’ I whisper in my little boy’s ear as we cycle through the city, ‘where those laughing people are playing table tennis, there used to be a wall.’ He absorbs it silently. He’s five. Clearly, he’s not ready for such layered ways of seeing – and why would he need to perceive things that aren’t there? Some part of it sinks in, however. At home, he constructs a wall from Lego; whoever clambers across pays with his life.

You never fail to ask me about my son. Your words betray an preoccupation with his very first memories, with the moments he’s forced to relate to a world that moves beyond the protection that I, as his father, am able to provide. I always have the impression that, in doing so, you’re saying something about yourself. It’s a particular obsession of yours which, I’ve come to understand, comes to light in your drawings. These hark back to the febrile intensity of childhood visions: images that recur time and again, with which one arouses or torments oneself, the symbolism of which becomes graspable only much later, or maybe never.

Perhaps you would say: less and less.

This past spring, before moving here, my son and I sauntered across a museum’s idyllic courtyard when a man came towards us on bare feet that were blackened from wandering. We were about to sit down in the sun to eat. The man emitted some hoarse sounds and rubbed his stomach with a miserable expression. I offered him a bulky double sandwich from our lunch box. That’s when he formed an ‘O’ with his lips, pointing savagely at where his teeth should have been. I awkwardly made it clear that I had nothing else to give, at which point he shook a clenched fist in my face. He briskly turned around and left the courtyard.

After a moment’s silence, my son asked me why the man had no teeth, and I realised this moment would stay lodged in his mind. It led to our first conversation on war and fleeing, though I could only guess what had happened to that man – a lack of answers further amplified by the wordlessness of the exchange.

It is an unmistakable privilege to be an artist living abroad. It also has an aspect of a child’s guilelessness and shelter. The city seems to open itself. It is no coincidence that, since my arrival, I’ve been handed sets of keys from every direction. Keys to gates, fences, a house, a studio, a gallery, a kindergarten, a freight elevator (‘160 tons per square meter’ cannot be right, can it?) – even to a garden in the outskirts. Like a postman, I need to ponder which sets to put in my pockets when I leave home. In a sense, art itself is a key to the city.

This makes it all the more disquieting to come face to face with the wretched who came here to seek asylum, and whose experiences have scarcely been recorded. I doubt if their diaspora will be written about and traced back with a similar meticulousness as the collective traumas of the Occident. It may be argued that the life stories of modern refugees, precisely because they’re so raw, so particular, and so unprocessed, weigh down on this landscape of memories just as heavily. What have they seen? What inner vocabulary of symbols do they carry with them? And what do they see when they look at me?

It does give my own walks around the block – and my presence here as an artist – a hint of futility and obliviousness; that’s why I feel the need to write about it. In order to render perceptible the obverse of this condition, and to put my finger on the strange inversion that takes place once you’re without worry and at ease within your new surroundings. For that is a moment of empty-handedness, when the space around you gives rise to introspection, to a renewed unearthing of trauma.

On my walks, I’m whistling and humming Hanns Eisler’s exile music. Eisler was a socialist, a comrade of Brecht’s and, for the longest part of his life, a Berliner. I’m captivated by his Ernste Gesänge (‘serious songs’), composed in 1962, the year of his death.[5] They are delightful, but very melancholic. ‘Many have tried in vain to say what is most joyful in joy / Here at last, here amid sorrow, I find how to express it.’ That’s a stanza by Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843); Eisler opens with these lines.

His affinity with Hölderlin, so dear, after all, to the German, or perhaps more precisely the East-German soul, is one of exceptional tenderness. As you may know, the hypersensitive poet never fit in anywhere, and once, having strayed far from home yet again, he returned to Germany on foot, completely neglected and unresponsive, after which he spent the remaining forty years of his life in a condition of insanity.

Eisler’s own life story is one of prolonged exile. When the Nazis rose to power, his music was banned, forcing him to flee to the US. In the end, however, he was expelled there too because of his ties with communism. Thereafter, he lived in the GDR. A blend of bitterness and homesickness is encapsulated in the song ‘Asyl’, which he wrote in Hollywood, drawing once again from lines by Hölderlin: ‘And that I too may have, like others, an enduring place / Be thou, O song, my kindly refuge.’

Aptly delineating the attitude that animates these songs, one expert uses the term ‘inner emigration’.[6] Is this a condition you could relate to? Your work, I believe, is firmly rooted; it harbours an extremely local quality, something ‘heimisch’, so to speak, or unreservedly at home. That is something I’m searching for myself, not least because I cannot escape it. At the same time, it is inseparably bound with a restless hankering for that which is ‘unheimlich’, or ‘uncanny’ – and that is something one could only explain by some strange dialectic.

On one of our first days here – sun-drenched, untroubled – my son and I ambled aimlessly through the streets, ending up in a small serene cemetery. After pressing our fingertips into the pockmarks of a mausoleum’s bullet-ridden side wall – it had probably served as a makeshift bunker during the Battle of Berlin – we idled in front of an information sign. ‘Dad, there’s nothing here, come on.’ That’s when I discovered that Eisler lay buried there. We wanted to add a pebble to the row on top of the headstone, but there were none to be found. We could have pried a cobblestone from the paving – they’re called ‘children’s heads’ in Dutch – but that would have taken it a bit too far.

Nickel

[1] Hanns Eisler in conversation with Hans Bunge, 1961. Eisler refers to a Hölderlin lyric he set to music for his ‘Hollywood Song Book’ in 1943, which Brecht privately criticized because he thought its pastoral depiction of Germany was ‘nationalistic’.

[2] Letter by Pieter Slagboom, 11 April 2017.

[3] Walter Benjamin, The “Berlin Chronicle” Notices (translated by Carl Skoggard), New York, 2015: Publication Studio, p. 5

[4] The Heavy Load-Bearing Body is a concrete cylinder of 12.650 metric tons, built under the command of Nazi architect Albert Speer in order to find out whether the sandy Berlin soil would be able to support the colossal structures he had envisioned for Hitler’s megalomanic ‘Welthauptstadt Germania’.

[5] My reference is the latest release with baritone Matthias Goerne (Harmonia Mundi, 2013). The English version of the original Hölderlin lines is taken from the liner notes.

[6] David Blake (ed.), Hanns Eisler: A Miscellany, Luxembourg, 1995: Harwood Academic Publishers