Foreword

by Roos Gortzak

Als je een ander dan jouw eigen deel van de wereld

kon zijn, wat was je dan? Als je een dier was

een gewelf of grond, een ander mens —

en dan het verband met wie je bent.

If you could be another part of the world

than your own, then what would you be? If you were

an animal, the heavens or earth, a different person —

and then relate it to who you are.

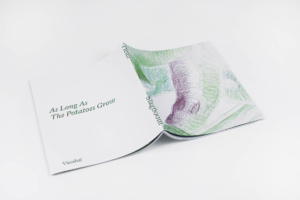

These are the opening lines of Anna de Bruyckere’s poem “Zelfkennis” (Self-knowledge), from her debut collection Voor permanente bewoning (For permanent residence). They came to mind when I was leafing through the draft of this book. A book that follows Pieter Slagboom’s exhibition As Long As The Potatoes Grow. A permanent residence for images of the artworks that could temporarily be seen in Vleeshal—together with the artist’s words and those of Julia Geerlings and Martha Kirszenbaum.

The questions raised by De Bruyckere are questions that also preoccupy Slagboom. Who are we? And how do we relate to (living and dead) people and things around us? The book opens with a detail from the work Arched, in which a naked woman bends over a naked man in a coffin, while a dog looks on. On the next page in another detail from the work, we see one dog diligently sniffing at the woman’s anus while another addresses his nose curiously toward the male genitalia. This sets the tone for the book, in which Slagboom advances his investigation into mankind’s relation to life and death, to sexuality and death.

These first images of details are followed by an installation photograph of the exhibition in which you look between two works at a third. In this third work, you descry a body lying flat, buried beneath geometric shapes. About ten pages later, you see a photograph of a visitor looking at this work. She can be seen from head to toe, has her hands in her pockets and is looking at the figure lying flat, of which only the feet, out-stretched arms and the top of the head are pictured. Crushed by geometric shapes? Blocked by the rational systems with which we try to gain a grip on the world? The man with whom the book opens, looks more alive. He has maintained his form, even if lying in a coffin. Is the woman bending over his body to breathe new life into him, or to guide him on his transition from life to death?

In his work, Slagboom sketches possible new scenarios for the transition from life to death. Does someone die a happier death if surrounded by people who make love and possibly celebrate new life? In his article “After Life” in the magazine BLAU International, Oliver Koerner von Gustorf says that Slagboom’s work is about “a crucial kind of care, about accompanying the dying, helping them to consciously experience all the phases of death, about transitioning into a new incarnation”.

The combination of sexuality and death is not commonly widely discussed. Slagboom considers it important to deal with this topic openly. He therefore represents it in his work in such a way that you cannot turn away. He introduces animals to bring the other senses into play. In the interview with Julia Geerlings and Pieter Slagboom included in the book, the artist expresses it well: “The animal gets something moving that is blocked in the human.”

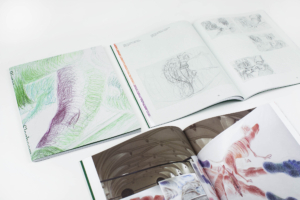

In the exhibition, Slagboom seemed to have taken on the role of the animal: he got the visitor moving, to free up possible blockages. For the ten works in the exhibition, he thought up a special track, based on the narrow street plan of Middelburg.

The works overlapped and formed a unity: they became spatial and dispersed the subject throughout the entire Vleeshal. It caused the visitor to be unavoidably pressed closely up against a painting one moment, and the next to find himself in an open space where more distance could be taken from an image. Time played an important role in these large-scale works; time to move through the track and view the artworks, to discover recognizable images in the colors and shapes.

Moving through the space, being aware of your body, your feet on the ground, relating to the human figures in works that were larger than you: these were essential elements of this exhibition. In this book, the human figures are smaller than you. You will most likely be sitting still while you leaf through this book. Take your time to go back and forth, to leaf back and skip forward, to be aware of your body and smell the book. And to cherish the hand lovingly stroking the hair on the final page.

Roos Gortzak is an art historian, curator, critic and director of Vleeshal in Middelburg.

I’ll Be Your Mirror

by Martha Kirszenbaum

“When you think the night has seen your mind

That inside you’re twisted and unkind

Let me stand to show that you are blind

Please put down your hands

‘Cause I see you”

The Velvet Underground, I’ll Be Your Mirror, 1967

In his 1967 cinematographic masterpiece, entitled Belle de Jour, Spanish-French filmmaker Luis Buñuel brings to the screen the surrealist blurring of fantasy and reality, fetishism, sexual perversion and blasphemy. There he relates the story of Séverine, a deeply disenchanted Parisian bourgeois housewife, interpreted by the inimitable French actress Catherine Deneuve. Lost in her own masochistic fantasies, Séverine, onto whom all sorts of sexual perversions could be projected, finds erotic liberation through part-time work at the upscale eponymous brothel, Belle de Jour, leading to complex psychosexual fantasies. In his large-scale, softly drawn pencil drawings and installations, particularly in his recent exhibition As Long As the Potatoes Grow presented in 2019 at Vleeshal in the Netherlands, Pieter Slagboom reveals, just as in the cinema of Luis Buñuel, and particularly in Belle de Jour, a multifaceted realm where voyeurism, frustration, pleasure, and dream subtly entangle.

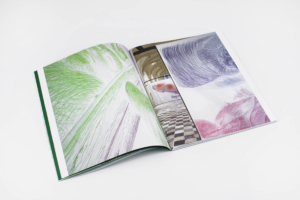

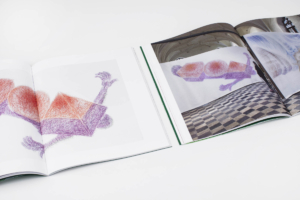

Life, sex and death seem to constantly dance a frenzied tango throughout Pieter Slagboom’s practice. In several of his colorful drawings exhibited at Vleeshal, orgy scenes take place inside of coffins while a delicate color code distinguishes the figures that are dead — drawn in orange or purple, from those that are alive — drawn in green. In another work, the black and brown tones evoke death in its frightening and crude representations. Elsewhere, a woman is sitting with her genitals applied to the face of a male corpse lying in a casket. More generally legs, bottoms, faces and curls repeatedly intertwine in a sexual climax that seems to precede an imminent death and a possible rebirth. Further in one of the works, the head of a dying man is surrounded by two penises and a vagina coming onto his face, expressing how fertilization is incorporated into death. A soft and delicate, if not romantic, drawing depicts two purple heads tenderly held by green hands, with curls of hair twisting around a finger of one hand, surrounded by a vagina and a penis pressing against the heads. The raw beauty of the work somehow evokes French artist, writer and filmmaker Jean Cocteau’s 1950 film Orpheus, in which the director’s taste for magic and enchantment is expressed though simple but dramatic effects to show his characters passing into the world of death by stepping through mirrors. “We watch ourselves grow old in mirrors. They bring us closer to death”[1], writes Cocteau as he films the blonde curls of his muse and main actor, Jean Marais. In a similar way to Jean Cocteau, Pieter Slagboom seems to position himself as a mediator poised between life and death. In medieval times, the French expression la petite mort [little death] started to be commonly used to describe the brief loss or weakening of consciousness and, in its modern usage, specifically refers to the sensation of orgasm as compared to death. Orpheus, just as the depicted figures in Pieter Slagboom’s drawings, must experience successive deaths or orgasms to reach a certain form of immortality.

The artist’s visual practice appears to be deeply rooted in surrealist-inspired representations of fetish and forms of pagan esoterism. His works on paper take us to explore eccentric orgies and death rituals, somehow evoking spectacular ceremonials of ancient civilizations such as Roman bacchanalia that would combine sexual freedom and ecstasy or pre-Columbian funeral rituals. Hair, naked feet, and dislocated bodies all appear as obscure objects of desire depicted in scenes that suggest rites of possession and transformation. The fetishization of body parts, such as feet or eyes, profoundly evokes not only the cinema of Luis Buñuel but also the poetry of André Breton, the French ‘pope’ of Surrealism, and his 1928 autobiographic novel Nadja[2], in which he chases a young woman met by chance in the streets of Paris and repeatedly portrays her persona through the description of her eyes. Surrealist protagonists and objects tend to merely exist through the metaphorical elements that provoke the fascination of their creators. One of Pieter Slagboom’s drawings depicts a dismantled androgynous character drawn in brown and purple — the colors of death, and its erotic pose and baby figure seem to evoke Hans Bellmer’s Doll from 1935, an articulated construction of wood, plaster, metal rods, nuts and bolts representing a young girl. A disturbing sculpture, Bellmer’s doll embodies a number of qualities of the surrealist object: subversive and erotic, sadistic and fetishistic. The figures depicted by Slagboom comparably open a reflection on bodily wholeness and sexual identities. Another crucial aspect of the surrealist aesthetic is the importance of chance, whether through automatic writing, wanderings or random encounters. The artist’s installation at the Vleeshal is composed as a labyrinthine architecture based on a map of the city of Middelburg, a medieval fortified city with narrow streets. The exhibition takes the surrealist form of a maze you cannot escape, and in which viewers lose themselves randomly, moving from small corridors to large open spaces into a physical experience of hazard and intuition.

Pieter Slagboom’s ritualistic and mystical approach to artistic narrative feels slightly disturbing, as the sexual power roles of his protagonists and themes seem to have been reshaped and deconstructed. Here animals, men and women share an equal status in their relationship to life, death and orgasm. In his prominent The History of Sexuality[3], developed between 1976 and 1984, French philosopher Michel Foucault examines the emergence of sexuality as a discursive object and a separate sphere of life. He interrogates why sexual activity and sexual behavior have become the objects of moral preoccupations and ethical issues. In his sometimes ambivalent drawings, Pieter Slagboom depicts a liberated, if not perverted, form of sexuality including animals and dead bodies, placing his provocative reflection at the level of morality and ethics. What characterizes modern sexuality writes Foucault, is not to have found its nature or reason, but to have been denaturalized and thrown into a void where it only encounters a thin limit. Humor and the absurd are also at stake in Slagboom’s frequent depiction of characters with disproportionally large feet and hands, somehow recalling the grotesque aesthetics of graphic novelist Robert Crumb, a key figure of American subculture and the underground comics movement. The aesthetics of both Slagboom and Crumb bring a particular attention to detail and satirical edge through their graphic and quite disturbing portrayals of sexuality and psychology. Even the title of the exhibition, As Long as the Potatoes Grow, seems quite incongruous given the overall complexity of the themes and representations conveyed in the exhibition, yet it unveils a philosophical and stoic message of stillness and confidence. As long as simple things carry on, everything will be fine.

Another noticeable aspect of Slagboom’s practice is the role attributed to women in his drawings. Describing himself as having been raised by 1960s feminists, he often depicts female characters as a powerful and positive presence, bringing men back to life. In the drawings female genitalia lie in the upper part of the pictorial composition, omnipresent and omniscient like the sky, drawn in blue on top of a man’s red body. Here, women appear as the active and dominating force in the hierarchy of gender power structures. One of the works presented at the Vleeshal exhibition presents a reversed traditional sexual act, where the woman’s genitals are penetrating the man’s. In some ways, this female depiction evokes the image of women giving life through giving birth, which has led to what French sociologist Mona Chollet has called the “fear of the witch”[4], describing a mix of fascination and fear developed by modern societies towards women due to their extraordinary power to give life. Furthermore, Pieter Slagboom seems to have inherited from his generation coming to age in the 1970s and 1980s a way of rethinking the relationship to family, to the other and to the body. Inspired by the photographic medium — his father was a photographer — and its capacity to express profound forms of intimacy, Slagboom refers in his compositions to several photographers, such as Diane Arbus and her radical portraits of American outsiders and freaks, who photographed her subjects in familiar settings. Here the boundaries between artistic individuality and assimilation within a family appear to be on thin ice. The notion of family can also be conceived as a group of friends or acquaintances of elective affinities, as in the work of Nan Goldin, whose practice has captured intimate moments of love and loss. Goldin’s characters from the 1970s and 1980s New York subculture scene experience ecstasy and pain through sex and drug use, they revel at dance clubs and bond with their children at home and they suffer from domestic violence and the ravages of AIDS. Similarly, the life, the love and the death of Pieter Slagboom’s protagonists come together into a hypnotic and intimate piece of art — an endless cycle of birth, sex and passing.

[1] Jean Cocteau, The Art of Cinema, London and New York: Marion Boyars, 1992.

[2] André Breton, Nadja, New York City: Grove Press, 1928.

[3] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1, New York City: Random House, 1978.

[4] Mona Chollet, Sorcières, la puissance invaincue des femmes, Paris : Zones, 2018.