Pieter Slagboom interviewed by Erin Leland

September 9, 2020

Erin Leland: Could you talk about the title of your exhibition, Saturated Manuscript?

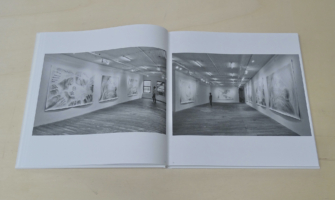

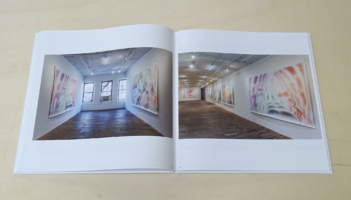

Pieter Slagboom: Saturation originates in my way of working with color, where form pops up sometimes in the monochromatic. And manuscript comes from the handwritten – I think drawing also belongs to the handwritten. In chromatic and monochromatic saturation I developed a technique to unveil the drawings in various tempos. To tear up the drawing apart in some ways. Monochromatic parts do not want reveal themselves entirely, as the monochromatic technic is a kind of a curtain. Manuscript refers to the fact that the project for Bridget Donahue has story-telling aspects also. The project is not only aesthetic. The works are anti-illustrations. Well, and here starts the whole complicated, multi layered significance of this show. Bridget Donahue is a long space in which the viewer can take a long walk. It is precisely this walk that activate the drawings on our retina.

EL: Drawing is the most immediate way to communicate. To put pencil against paper.

PS: Drawing is a trade very close to us. It’s a direct way of expression. You don’t need too many tools. You only need a pencil.

EL: Directness is part of a contrast in your work, where a claustrophobic space exists between people – an extreme closeness – and at the same time the attempt to zoom out and witness the scene from far away. The enormous scale of the drawings suggests that the audience would have an omniscient view, but the drawings immerse us within the compressed dynamics between figures, like a micro lens focusing the expansiveness of the ocean. How did compression and distance gradually combine into the visual space of your work?

PS: I’m interested in that contrariness. People try to board a plane to travel 5,000 miles away. A whole big adventure happens within compressed space. It’s a reaction to global developments that the most important things actually are very nearby. That space is actually within yourself. And if somebody else comes into your life, it becomes twice as complicated. The drawings are not literal representations, but poetic fusions of contradictions and conflicts.

EL: In the drawings, the women appear to be the more dominant force.

PS: The women are reviving the men, who are actually dead. People are coming back. That is one hidden meaning in my drawings. The female genitalia are common to the works in the gallery, because they are on the top of all the drawings. This dynamic forms the organizational principle of the installation. For me, as a man, the woman is much more important.

EL: Your drawings are also full of bodies laying down. Usually the males figures in your drawings appear to be asleep. The body could be dead or could be resting. There’s an ambiguity between death and sleep. Does the dream space of your drawings emerge from an image seen in sleep, whether permanent or transitory?

PS: The composition plays with these various realities. Dreams play a role in it. When I walk somewhere, I exercise different kinds of consciousnesses and subconsciousnesses. Things can pop up within myself seemingly without reason. And in the total design of the exhibition, the women are in the top of the drawings and the males in the bottom, because that’s what I experienced in my youth.

EL: When you were a child, you experienced the female as more dominant?

PS: Yes, because I was raised by feminists.

EL: Which made you encounter your own maleness as more submissive?

PS: Well, I actually looked for my maleness in another part of the world. That’s when I went to the USA.

EL: The experiences of your youth still come through your drawings.

PS: All the experiences of your life stick with you. For example, if you have children. If you start a relationship. Let’s say life consists of five levels and youth is one level. These images recur every time. Some images never go away. In my work there is always a mixture of old and contemporary.

EL: And repressed moments, images that you may suddenly remember and did not remember before, surface.

PS: Right, so my work is not autobiographical, but the biographical level gives it energy.

EL: To me, your world of alchemically colored, alien figures relate more like giants than people. They take on an allegorical rather than representational character.

PS: I want to express that small things are actually very big. I want to magnify the smallest things in ourselves, like genitalia. In my opinion, the world turns around genitalia, because procreation births life.

EL: And survival. The act of birth is full of pleasure and pain. However, in your giant figures, there is no pleasure or pain expressed on their faces.

PS: I tried to be neutral. I wanted to bring attention to the body parts.

EL: The images become more symbolic through the detachment from emotional experience.

PS: The emotional experience comes symbolically through the intensity of color, through saturation and monochromatic parts. The sexual stimulation of the woman in the top of the drawings and the sexual stimulation of the man in the bottom of the drawings accompanies death. There is an equalization of life and death that I am trying to give shape to in my work. Logical or illogical or dreamlike or reality. If I start these dreams, these illogical thoughts, and I take a walk on the street, I see that reality is not far away. People behave very gently and not gently at all.

EL: The drawings of revival attempt to find the beginning of life at the end of life.

PS: I try to examine conventional thoughts about life and death. For instance, does the image of death look like a big black car coming and rolling you away? Sometimes I doubt that is the right image. Death occupies a monumental space in our life. It is not negative and we should not be afraid of it. Christianity teaches us to be afraid, but I am trying to look at death another way.

EL: We cannot think of life without thinking of death. Death is contextualizing. Death is also the most repressed thought. We are all trying to forget about the possibility of death on a daily basis.

PS: Instead of getting energy from it. Our whole society is built around avoiding death. 200 years ago it was different, and death was brought into the understanding of life, such as in Caspar David Friedrich paintings of the Romantic period in Germany, where death inhabited the philosophy of the whole culture. And then it disappeared, I think, after the Second World War, which made a fierce taboo of these thoughts.

EL: Because people experienced too much closeness with death.

PS: Yes, because death was used for oppression and to raise fear within people. War is based on fear of death. So, if the fear for death is not there anymore, war looses a goal.

EL: War can also be enacted remotely now, preventing direct contact with death.

PS: Historically, and in the time of World War II, war was an idea of how much men could conquer. There were no women involved in direct, front-line combat. Other than death, another fundamental force in the world is pregnancy, biologically experienced by women. In my work, I am asking if there is a difference between women and men. What is the difference? Or, are women and men not different?

EL: Of course, in our era, gender is understood as a changeable, cultural construction.

PS: Right. There is no one hundred percent man, no one hundred percent woman. As I think a person is in fact not one person but multiple people at the same time, the woman is the realization of this feeling when she is pregnant. She is at once multiple people. And multiple minds. Pregnancy makes a very large difference between men and women.

EL: People want to turn against biology and turn toward performance and choice, to point to the idea that in every era, people have been performing genders according to societal norms. And that it is possible to perform them differently.

PS: In my earlier book of drawings, salt, there are two large drawings of one circumcised man and a humiliated woman whose clitoris is cut. These are cultural rituals that I study.

EL: Would you say you are pointing to the grotesqueness of a sexual aesthetic imposed as a cultural preference? Or to the visceral experiences of the human body?

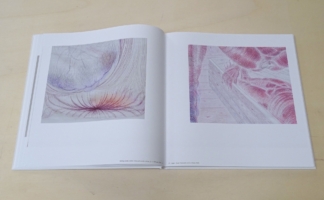

PS: Religion and culture have narrow minded aspects. I am aware they keep society together in some way. But for the thinking of the individual, who is observing nature and biology in her or his own way, religion and culture work to narrow the mind. Also in our western world, the independent thinking is under pressure. These are thoughts going on I’m my head. And when I feel the pressure on this idea, I start making many small studies, and they are sharpening and sharpening, and then I decide to make one bigger in black and white. And then I make a color plan. The color detaches the subject matter in order to clarify the image but also to confuse the image. Ephemeral color complicates the perception of the walking viewer by slowing down the images. Colors are introduced sometimes as being functional and not as being aesthetic. The ephemeral colors are rather fluid leads. After a while, the spectator will make a whole out of it.

EL: The drawings look as if they are constantly in motion, a refection of repeatedly moving thoughts in rotation. The moving, drawn lines connect to animation. Do you consider animation an influence?

PS: Like a moving illustration, like a cartoon? No, I am not influenced by animation, but I do study film. I have even subtitled my work in my book, Parma Violet, referring to some directors. In some periods of my life, I studied Ingmar Bergman for his relationship between women and men.

EL: Subject matter in your drawings is very explicit, while continuing to be abstract. Hair is more recognizable than specific body parts, at times, and the colored pencil line itself is the most recognizable of all.

PS: Things that are contrary are at one time the same. A drawing of a birth is not only a beginning, but a depiction of a boy being born out of a feminist. As well as being a self-portrait. And a moment where male and female genitalia can come together.

EL: In many of the drawings, there is a merging of the birth canal, the baby, the umbilical cord, the sexual organs. They all start to become inseparable as shapes, which positions the viewer between and inside of anatomy, between male and female, into an ultimately ambiguous space.

PS: I want to stage contradictions. For me it is still a mystery what nature and biology have in mind for the human being.

EL: Contradictions bring another question to mind about your simultaneous role in making your work and in raising children, and whether your children understand the sexuality depicted in your drawings. Do they have a response to it?

PS: I think parents do not have to do with the feelings of children. And it turns out that children have a large life during their childhood that is independent of their parents. Intuitively and biologically, children go their own way.

EL: Your work addresses the distance between a parent and a child. On an innate level, perhaps children and parents do not want to know about each other’s sexuality, because there is a closeness to incest which is biologically averse to procreation.

PS: That’s right. It’s against survival. In American art, there are many examples of the boundaries between artistic individuality and individual assimilation within a family unit, for example, in the work of Emmet Gowin and Diane Arbus among others. I do not not want to hide myself, so it takes some time and can be confusing and uncomfortable, but my children do not like me less for it.

EL: You have to maintain your individuality as a human pursuing your interests, and that is sometimes in conflict with raising a child.

PS: Yes. You try to incorporate things into your family, but at the same time, you keep your own life. In a relationship, it’s also a bit the same, where you share a lot with your partner but not everything. It’s a very complicated dynamic actually. Sometimes I say you are married to your children and not married to your wife. Trying to decide how to draw the boundaries is intense.

EL: The birth drawings question, too, how a culture might raise a child as much as a parent raises a child.

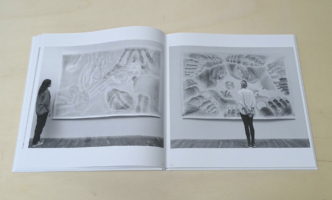

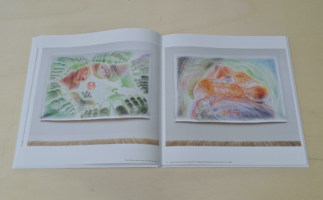

PS: I like to try a birth drawing, since as an artist, it is a drawing you never do. It can be too popular, the emotion too easy. Of course, birth is not easy. But I like the challenge of working with an easy emotion, and I like to provoke the assumed ease of this emotion in society. Maybe we could look here at the drawing entitled Shifting Scale. This is an example how I try to divert the focus of the viewer. The head of the body comes on earth between the clitoris and the anus of his mother. I magnified the clitoris and the anus and gave them a bit stronger color than the head of the baby. Here I subdued the main subject and I accentuated the side issues at that particular moment. So I force the eyes to look beside the main subject. My work is an eye rolling kind of perception. Hard and not self-evident for our retina. In which the movement of our body and head also plays a role.

EL: Standing in front of the drawings, I do not feel embarrassed or shocked. The conversations the drawings provoke feel more confrontational than the drawing itself. The drawings generate a whole different set of texts.

PS: Yes, conversations are a jewel. Speaking about the work goes both ways. By answering a set of questions, I also know something about the viewer. Your questions tell me something about yourself. How do you feel people will view these images in New York?

EL: I always have a hard time predicting how someone will respond to a work of art, but right now, art in America is addressing life and death as it relates to political strife and racial inequity. Through the valuation of life and death, artists are also addressing brutality and gentleness. Through the world at large, there is a concentration on how boundaries in society can be rewritten as unbiased laws. I think your work addresses these concerns through the symbolic rebirth taking place among the figures, who are acting out positions of dominance and submission as they relate to gender and culture, existing in a universe unto themselves not immediately connected to the past or future. These are timeless questions.

PS: I am interested in showing my work to new eyes.

EL: There is also a moral aversion towards nudity in America that differs from other cultures. In the United States, nudity is often tied to sex and therefore felt as a provocation.

PS: Yes, it’s newer in the United States, whereas in Germany or Japan for example, sexuality was always more on the table. Do you think relegating sexuality to a private realm comes from the Victorian period in England?

EL: I think it comes from Christianity. But of course, on the other hand, we have a huge amount of visualization of the body in film and advertising. Think of billboards in Times Square, for example.

PS: I experience that as aggressiveness more than tenderness.

EL: Maybe you are bringing tenderness into these topics.

PS: I hope so. I like that idea. Let’s look through the individual drawings. Do you have the feeling that you more or less see what each drawing represents?

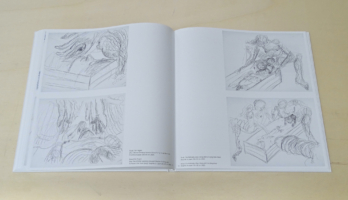

EL: Here for example is a woman leaning over a baby. The baby is squashed between her feet and a man in a coffin.

PS: The title is Artificiality, and in parentheses, (Also: Birth On Dying Male Head. Also Hair). I find artificiality important in my work and in my thinking. Artificiality brings me into a fantasy world where things happen that usually do not happen. But maybe could happen. An in-between world which gives me space and opportunity.

EL: Is the implication that the woman is giving birth to a baby whose father is in the coffin? Or is the dead body anonymous?

PS: No, the people are all symbolic. Sometimes I like to play with very flat ideas. Someone might say that giving birth to a dying body is too easy. I like to play with very easy and direct ideas.

EL: Clichés you mean?

PS: Exactly. A cliché, but a cliché I’ve never seen.

EL: And there is actually a lot of complexity in clichés.

PS: Yes, because they are archetypal images also. Let’s look at the next drawing on your righthand.

EL: This one looks like it’s a human face inside a vagina.

PS: Almost. It’s the dying head of a man with aroused female genitalia of three women surrounding it. So it’s a fantasy or cultural ritual where people die while others are aroused. Or, could dying have been eased if surrounded by sexual arousal?

EL: So then it is like you are creating your own death ritual. You recently mentioned that in a drawing, you put all of the colors in the coffin. Whereas the onlookers are mono chromatic.

PS: I gave very many colors to the dead body. We should not be afraid. The death ritual is a way to soften the burden. Everyone lives with burden.

EL: Whether it is exposed or not exposed.

PS: Yes, or translated into something else. Yet, I find it important that the drawings stay mysterious. And at other times I want people to see what I mean.

EL: The drawings are between being explicit and implicit.

PS: Sometimes, during the night when an image is forcing itself on me or attacks me, I get up, sweating, and think “Oh no, this is not possible”, and then I wake up, and say “Ok, I’m just trying and I’m going to draw it, but I’m not going to show anyone – that’s the next step”. And then it’s drawn, and I say, “Ok, I’m going to show it to only one person. Go on. Keep going.” And then, it grows and grows. A kind of talking oneself into it.

EL: Talking oneself into exposing what is internal.

PS: Yes, it’s kind of winning oneself over. In the night, the strangest things come up.

EL: The most layered images reemerge, visualized again in your drawings of sleeping people.

PS: Fear occurs when the drawings become the most intense. Fear has a function.

EL: The next drawing is my personal favorite. The circle of giant green feet reminds me of a specific dream I had as a child, about a green giant in the kitchen pantry.

PS: What it brings together actually is a design of contradictions. What is real now has been imagined before. We live in phantasy.

EL: In order to make something real, it has to be imagined first.

PS: Exactly. I do not stop things from coming into my mind anymore. I make sketches to clarify ideas, frustrations, observations. It’s a way to empty the head and to refill the head. It’s a testing ground.

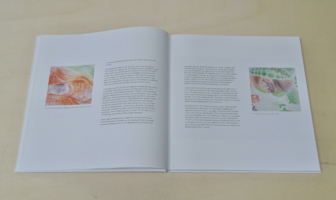

EL: While making your largest drawings, you mentioned that you invented padded finger covers to wear over the tips of your fingers. You said that they enable you to continue drawing, since otherwise your fingers developed small wounds from the pressure exerted on the pencil.

PS: I was disappointed because I could not feel the pencil anymore. The tenderness disappeared. So I use the finger covers for the large drawings when I press down every day for a whole week. I think you have to protect your fingers. Between the skin and the bone, finger padding begins to vanish, and the pencil makes contact with the bone, which is very very painful. With the pads, I can keep going on. I need large pencil sharpeners which have to be imported form the USA. With these machines the pencil is becoming sharp in an instant so I am not delayed in drawing action. This is important because making the form is a moment of continuous concentration where there is actually no time for sharpening. Every drawing project takes around 3,000 to 6,000 pencils.

Pieter Slagboom and Erin Leland conducted this interview on September 9, 2020,

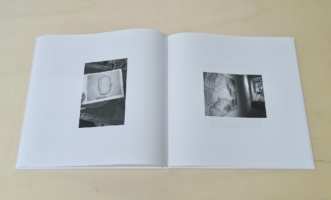

one day before the opening of Slagboom’s solo exhibition, Saturated Manuscript, at Bridget Donahue. The interview took place remotely, in keeping with the installation which had been conducted through a series of video conversations between the gallery in New York and Slagboom’s studio in the Netherlands during the international travel restrictions in place throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Colourful Room

Dean Kissick, January 2021

Some mornings ago, thinking about what to write here, cycling down Broadway toward Times Square, I passed a man walking in the other direction, dressed in robes like a Magi, and he fixed my gaze and shouted at me, “WHY ARE YOU DYING!” It’s a good question, though I don’t have an answer.

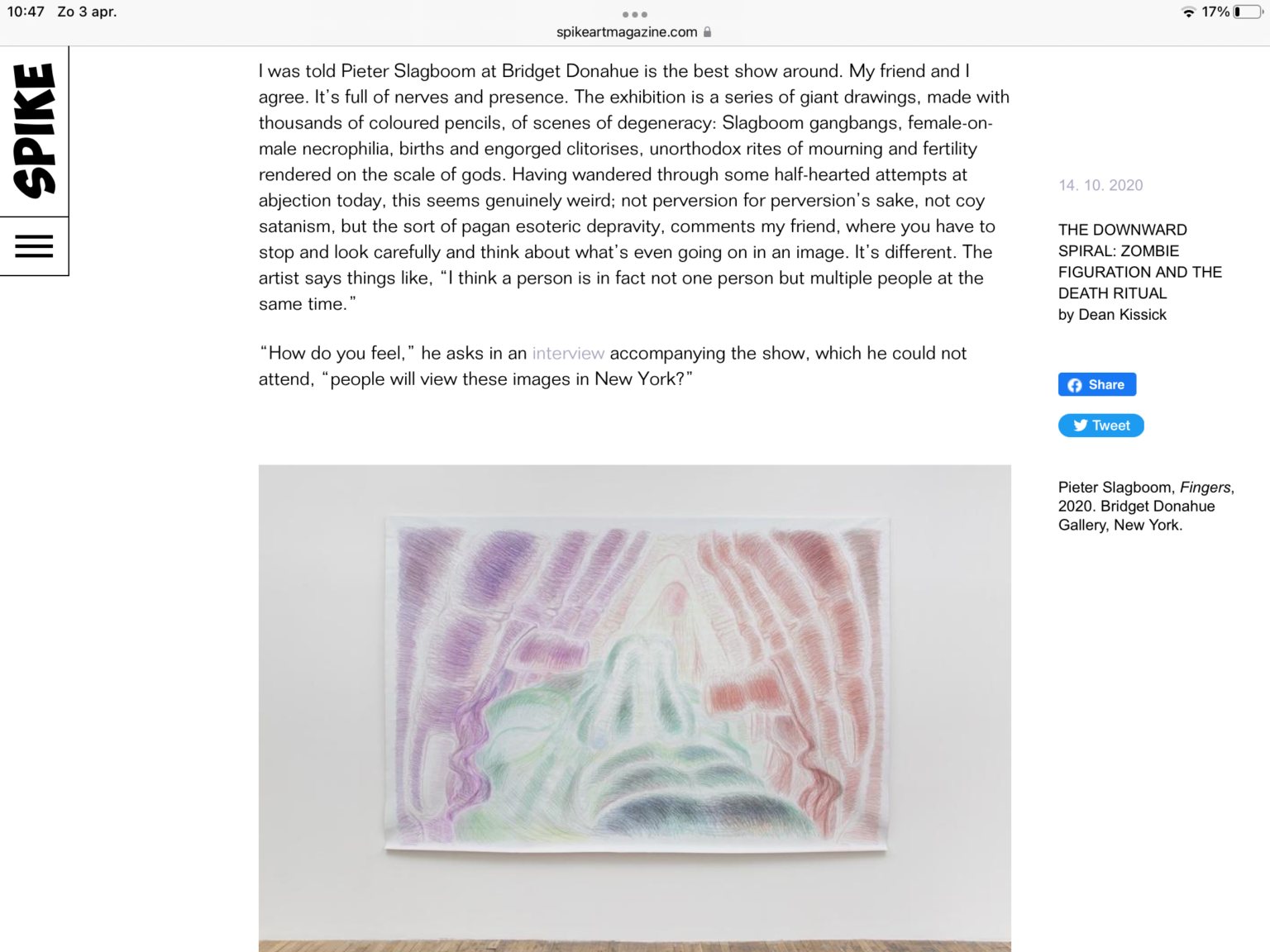

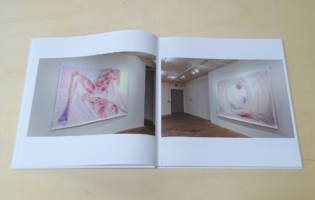

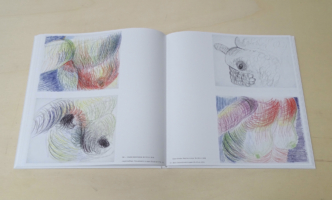

Saturated Manuscript opened in the fall of 2020, when Manhattan had come back to life and the streets were busy again. My friend and I climbed the stairs up from the Bowery, opened the door to the gallery, and turned right into a giant drawing (Poetic Flesh) that was hard to make sense of but had a great impact. It was like discovering a forgotten tomb, or abandoned spaceship; we wandered round and felt confused. The softly drawn colours pulled us in, and forms came into view. The exhibition was a series of eight giant coloured-pencil drawings of what slowly revealed themselves as strange combinations of dying and dead bodies, newborn babies and huge, swollen genitalia. This was the sort of pagan esoteric depravity, my friend commented, where you had to stop, have a breath, take your time and look carefully and think about what’s even happening in each image.

What we saw was surprising: a naked lady splaying open her legs and lowering herself onto a dead man in a coffin; a gang of women (above) and men (below) gathered around another corpse, clearly sexually aroused; a baby born with face pressed snug against their mother’s clitoris, and other unorthodox rites of mourning, and shimmering, psychedelic displays of fertility, rendered on the monumental scale. These seemed to be pictures of spirits, or celestial beings. Art seemed to be returning to its ceremonial origins: to magical images on the walls of the caves, to symbols, to scenes of possession and transformation. Not only were these images of made-up rituals, they were also made through a solitary ritual: an artist drawing his way through thousands of pencils, giving shape to private visions that would usually stay concealed. Those lyrical visions were broken up into drawings, and as we walked around them, certain themes became sharper. Walking a ring of the gallery evoked the journey of a newborn into our world, and the passage of the dead into another.

In New York that spring, six months prior, temporary morgues were set up outside hospitals, with refrigerated trucks, painted quickly over with a single wash of white paint, waiting beside them to ferry the dead away. Graves were dug in parks on the islands for when the cemeteries overflowed. But death was still somehow hidden from view. Even when the dying were everywhere, they remained hidden. One never knows what’s going on behind closed doors in this city. The only times I felt close to death were when I saw the swirling lights of ambulances parked outside apartment buildings in the dead of night. Death has felt uncannily absent throughout the pandemic; the dead are just numbers, they’re invisible. Today we’re surrounded by death but don’t acknowledge it. We have no idea of how to give voice to this tragedy, let alone any shared rituals for coping with it, or finding communal catharsis, or hope. While Pieter Slagboom began preparing this show before the pandemic, his enduring themes have come to feel particularly urgent and to rhyme with the present.

Similarly, while sex has traditionally been related to procreation, and later to free love, which offered a vision of a new type of society, it’s increasingly now related to nothing; it’s just one of many casual pleasures on offer, just another source of dopamine. Younger generations, such as mine, are losing interest in sex, and have grown too wary of risk. We fear sex and death, which is to say we fear our nature and the stories of our lives. We’ve lost touch with what we really are.

While belief systems like Christianity, or the new worship of virtuality and the artificial, have encouraged us to separate ourselves from our biology, and the old forms of spirituality with which it’s so entwined, Pieter’s images encourage us to return to lost and frowned-upon ways of thinking in the hope of finding different perspectives. He shows how sexual arousal is all around us, every day, everywhere we go; how it’s a dominant force that mustn’t be repressed. How biology is cruel and wonderful, and heavy with contradictions. Sexuality is a sensitive topic in every culture, but we don’t deal with it well in the 21st century. Perhaps it’s us, and not our ancestors, that are the primitives, he suggests.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, which were violent but sensual civilizations, and Egypt, which revolved around a spectacular death culture, ornate cults and rituals were developed, only to later be suppressed under Christianity; and now it’s too late to find out what was going on in those societies. Take the clandestine rites of the Eleusinian Mysteries in Greece: we still have no idea what was experienced in those caves. We’ll never know. The ancients took their birth and death rites to the grave. But the role of the artist, Pieter says, is to channel those primal emotions and give them a form: and in so doing, to hopefully tip our culture over in another direction. His way of dealing with mortality is not to ignore it, but rather to obsessively depict his own death, imagining funerals and eulogies afresh in vibrant new configurations and tones. In these fantasies, the passage of the dead is often accompanied by the sexual arousal of the living. His dreams are of dying surrounded by engorged neon clitorises. He proposes that dying, that passing through the intermediate world between life and death, would be less traumatic if we were surrounded by collective arousal, by youth and lustful fertility. He opens a space for the many deep and contrary feelings a death can spark in us, from despair and suffering, to joy in life. A death can make us feel many different emotions at once, and we have to give space to all of them, in order to grieve, and not be too afraid.

His figures are drawn larger than life here. Cabin, at the far end of the gallery, shows a dead man in his coffin. The coffin is large enough that our skeletons could dance around in there. Bodies become architecture also: the girl crouching over the dead man in the coffin covers him like a dome above a church, becoming a skyline. Holes turn into doorways. Corpses and orifices are hung at eye level, daring us to come closer. The world revolves around genitalia, where our lives began, so he represents them on a grand scale, as the ancients once did with their fertility cults, and their phallic maypoles children dance around in spring.

A vagina large enough for us to step into, resting on a throbbing penis big enough to ride, appears in Muscles. Apple-green hands hold a dying couple, and by association us, back from returning to the womb in Fingers II, preventing us from dragging ourselves back into our mothers. You can never go home again. Another piece, Fingers, shows fingers pressed against glistening vaginal lips and parted over sexes forming the walls of a cave, or the stonework of an old gothic church, rendered in the colours of stained glass. These images are massive but light and heavenly; they welcome us in rather than bearing down on us. Their bodies burn like phosphorescent roses. Just as the show’s title evokes the illuminated manuscripts of medieval times, strolling around it reminded me of wandering the second floor of Paris’s Sainte-Chapelle on a summer’s day, with light pouring in from every side, giving a feeling of having stepped into heaven.

In Toes, vaginas and breasts form a metabolic architecture around the dead. Resting on this beating sarcophagus are five massive pairs of feet. The figures above them cannot be seen, but we look down at the burial from their giants’ perspective, their gods’ perspective, floating around in space. The gallery wall is turned into a hole in the ground. Everywhere you turn perspectives are warped and twisted as if seen through a distorting lens. The next picture along, Poetic Flesh, shows a birth from the viewpoint of the baby being born. The baby has a large penis and is aroused. His penis, his mother’s clitoris, the umbilical cord joining them and their bodies glow amber together. Lines and colours blur. Male and female genitalia come together. An image of birth becomes an orgiastic aurora borealis, a swirling abstraction. Standing in front of it feels like hallucinating the beginning of your life.

These pictures tell a story but it’s a story that loops around like a Möbius strip. It has no beginning or end. It’s an endless cycle of sex, birth and death, which are shown to be parts of the same process. The exhibition conjures an experience of ritual. Its grand, immersive panels swallow us up as a colour field painting might, and carry us into another space in their arms. In this space we catch glimpses of new ways to die. It’s like a lost scene from Ovid: like we’re dying and surrounded by sexually aroused goddesses, gods, heroines and heroes.

Pieter draws rituals in which fertility gives meaning to death. These rituals may never take place, and don’t have to. His drawings allow forbidden things happen; things that won’t happen in our reality. By dreaming of death, this death in many colours, we might live without fear. There’s nothing to be afraid of. While these colours may appear unnatural, in that they don’t reflect how our bodies look, they point to another, invisible level of nature, and the powerful forces that drive it. Sexuality is envisioned as a bright and mysterious force that twirls around all of us: a mystical part of the cosmos, and the wonder and glory of life, rather than a specific desire located within the individual. A force that binds us all together from the beginning to the end of our lives.

To my stranger guest

By Julia Geerlings

March, 2021

She longs to fold to her maternal breast

Part of herself, yet to herself unknown;

To see and to salute the stranger guest,

Fed with her life through many a tedious moon.

After a long day I lay on the couch with a rooibos tea, and switch on the television to find Frankenstein 1931 playing on national TV. I recognize the thunder penetrating the lab instantly. Lightning bolts cast shadows of Victor Frankenstein and his faithful hunchback assistant on the walls. A mummified creature, bound to a stretcher, descends into the laboratory after the scientist engages a lever. “It’s moving…” “It’s alive… It’s ALIVE!” “Now I know what it feels like to be God!”.

I grab a handful of chips, put my feet up, and place my hands on my belly. I take the time to feel you moving inside me. I feel you twisting around my abdomen, kicking in my ribcage and using my bladder as a trampoline. This is my second pregnancy and it still feels surreal. You are inside of me, but you are not me. Your little body feels like a part of me. You are a guest I have not yet laid eyes upon, but I couldn’t be closer to you. I already feel a strong love towards you, my ‘stranger guest’.

As your movements increased over the last few months, and you explored the limits of my internal being, I became estranged from my body: my hips rounded, my breasts grew, my nipples darkened, my hair thickened and my gums grew sore. “Cells fuse, split, and proliferate; volumes grow, tissues stretch, and body fluids change rhythm, speeding up or slowing down. Within the body, growing as a graft, indomitable, there is an other. And no one is present, within that simultaneously dual and alien space, to signify what is going on. ‘It happens, but I’m not there.’ ‘I cannot realize it, but it goes on.’ Motherhood’s impossible syllogism.”

Almost two hundred years after Barbauld’s opening poem above, philosopher and writer Julia Kristeva describes the same haunted feeling. The line of the poem “fed with her life” has an ominous double edge: pregnancy often really meant surrendering your life to a stranger. For Kristeva, the maternal body is the epitome of abjection. The placenta simultaneously connects and separates mother and child. A pregnant woman literally embodies something foreign – an ‘other’ person – as much as she experiences foreign feelings and hormones.

In our literary and philosophical tradition, these topics have only been approached by male philosophers and theorists in an attempt to control, rather than understand the pregnant body. This violent superficiality has only recently been broken by female feminist writers such as Kristeva, who deepened our understanding of motherhood and the experience of pregnancy, and inspired me to rethink the distinction between myself and the other, between my body and mind, as well as the separation between life and death.

On the flatscreen of my living room, the monster lives, the monster kills, the monster dies, following the dark fate of his father, Dr Frankenstein. Our relation too, my stranger, is bound by a flirtatious relation with death. The prints of our ultrasounds, attached to my fridge, feature your tiny skeleton, dancing in the prenatal darkness. These images summon tragic memories of the times of Mary Shelley’s novel, when the risk of death during pregnancy was higher for mother and child. She had suffered the birth and death of an infant, and wrote Frankenstein while being pregnant again. Victor Frankenstein’s failure as a “parent” and the birth of the “creature” by reanimating dead body parts, have been seen as an expression of the anxieties which accompany pregnancy, giving birth, and particularly maternity. Shelley herself ended up losing five of her six children, of which she gave heartbreaking accounts in her diary.

I can’t wait to meet you, my little invisible being. When it’s time you will free yourself from my womb. Then, from inside, we shall waltz one last time together. I will ride the waves of contractions, while you crawl and spin through my pelvis. In the final act, you shall enter the ring of fire while I push you through the birth canal. If everything goes well you will arrive to the world here, at home, next to the couch where I’m laying now. That moment is losing you, like losing a limb and meeting you, my little stranger guest. A part of me that dies, and is reborn as a your mother.

To my stranger guest came together while observing and contemplating deeply about the drawings by Pieter Slagboom in the exhibition Saturated Manuscript at Bridget Donahue in New York City in 2020.