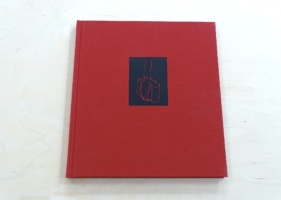

Vleeshal. Pieter Slagboom. Drawings.

Pieter Slagboom. Drawings

Published by Vleeshal

2005

Pieter Slagboom. Drawings

Published by Vleeshal

2005

Introduction

By Rutger Wolfson

In his recent work Pieter Slagboom has withdrawn from the physical world to an imaginary space in his mind. Over the past four years he has abandoned his installations and environmental works for drawings: drawings depicting his experiences in this inner world. Slagboom’s earlier architectural sculptures and his recent drawings could hardly be more different. Whilst the environmental works are cool, distant and formalistic, the drawings drip with emotion, irrationality and shit.

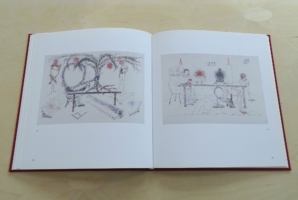

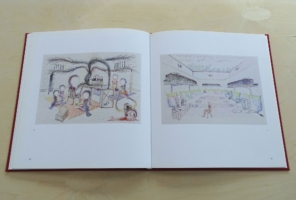

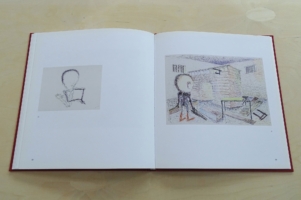

In his drawings Slagboom literally presents his inner world as a space. Sometimes explicitly: as a room, with proportions of a lounge. Other drawings are less specific, but viewers sense inuitively that the work is set in a space resembling a living room. The same kind of space, over and over again – possibly because Slagboom, as do so many of us, pictures the part of his mind where his thoughts unfold in a room.

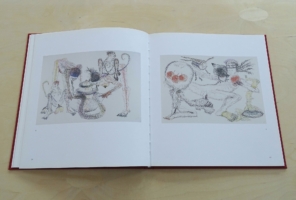

But perhaps there is another, more obvious, explanation. Slagboom’s home life appears to be the starting point for his work: a domestic setting as a mini universe, the size of a sitting room, where great universal themes are played out. Time and again, the matter at hand is the battle between the sexes – in which the male seems to be the weaker party. Slagboom captures this contest in a distinct scratchy style that is not aimed to please, but to irritate: to sting, and to needle.

Slagboom’s drawings do not disclose his private universe directly. He portrays his domestic life through a series of highly personal symbols. His spaces are occupied by women producing an endless flow of shit, which men then use to build houses. Elsewhere, reminiscent of Goya, men are brought before women’s tribunals. Men as children, women as mothers, biblical fruit trees, lemon squeezers, monkeys, birds, snakes, inland vessels and lavatories: these are all recurrent motifs in Slagboom’s work.

This symbolism takes nothing away from Slagboom’s candour. Although his motifs are mostpersonal, they do not form a smoke-screen for the artist to hide behind. On the contrary: those who study the drawings soon discover that the symbolism reveals rather than conceals – namely a compulsively honest perspective on the at times oppressive war between the sexes. Slagboom’s symbols stem from the frustrations in this battle: a personal conflict connected to universal themes, through which its cause is suddenly raised to epic proportions.

This is where Slagboom’s work derives its equally extraordinary as unexpected quality: its courage. His drawings are as sincere as candid and as bold as his earlier works were austere and formal. And so Slagboom’s move from environmental works to drawings turns out to be less drastic as it would, at first, seem.

Between myth and reality

By Florent Bex

Pieter Slagboom’s recent works forms a very remarkable ensemble. In part this is due tot he idiosyncratic style of drawing, but mostly it is because of the fascinating, personal, mythical world it evokes, in which unconscious images merge with recognizable scenes.

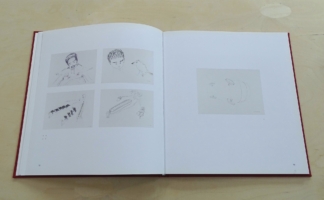

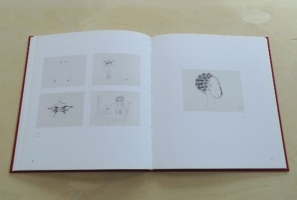

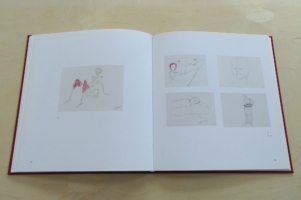

In these scenes all the depicted objects and figures are solely made up of a crisscross of twisting pencil lines, which spread organically within the given forms and contours. There is not a straight line to be seen anywhere, only flowing and waving lines which give the impression of having been sketched quickly and spontaneously. Nevertheless they don’t overlap the limits of the distinctively portrayed elements of which the scenes are composed. The drawing doesn’t delineate the themes for us, it merely suggests, and is simultaneously both complex and clear.

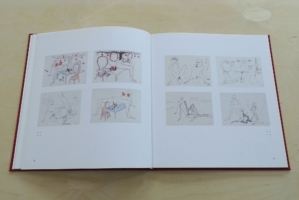

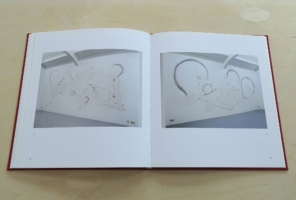

In recent years Pieter Slagboom has realized an extensive number of drawings, varying from small simple black and white sketches, to colourful and lavish sketches on sheets of 100 × 140 cm. For the recent exhibition in De Kabinetten van de Vleeshal in Middelburg he even worked straight onto the wals.

In every composition there is a balanced interaction between the parts that are lightly sketched with just a few lines, and the parts where the pencil strokes are darkly emphasized. The apparently free and spontaneous style of drawing is thus harmoniously adapted to the interrelated disposition of the depicted elements. It is precisely this combination of control and chaos, of the Apollonian and the Dionysian, which lends the work its particular charm. These two opposing forces are also constantly present in the iconography of the depicted scenes.

Two figures that feature predominately in a whole series of works are a child with a large head, and a woman usually depicted lying on her back on a table with her legs spread. There is little suggestion of the sexual woman, and even less of the fertiel mother figure. The woman evoked by Pieter Slagboom produces excrement rather than living matter, with which the child with the large head (the artist’s alter ego?) makes houses or trees. Is this a reference to the classic concept that woman symbolize nature and man culture, and that the latter prevails over nature? Form prevailing over matter? Or does the child, in his innocence of the game, seek to fathom the woman’s secret? For “the female body ensures the effective internment of the secret, as the unity which cannot be fragmented, as fluid solidified into a fixed shape.” (1) In any case the child is the maker, the creator who constructs things at his worktable. Thus the child probably is a metaphor for the artist, since “art is mainly a quest for the innermost female secret, a gaze prompted by the truth of her womb.”(2). Or do these strange scenes refer to unfulfilled longings? “Freud had a pronounced tendency to see art as a non-neurotic compromise between the ‘lust principle’, between the longing to realize unconscious unfulfilled wish fantasies and the prohibition on doing so.” (3) “Art is the modern person’s most bearable way of dealing with the absurd attraction to “nothingness’.” (4). George Bataille’s statement that art can be nothing oher than an “avortement merveilleux” (5) is certainly pertinent in relation to Pieter Slagboom’s work.

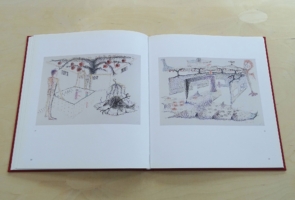

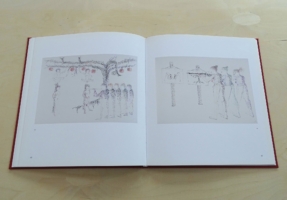

However the child constructs not only houses, but also large, branching fruit-bearing trees. Which tree from paradise does it represent?Is it the tree of knowledge, of good and evil, with the forbidden fruit, the tree of life and its inherent immortality? Os is it the tree that symbolizes the female principle, the nurturing and protective aspect of the primal mother? Or is it simply a symbol of fertility?

I don’t feel called upon to psychoanalyse the artist’s image and thought associations, and certainly not to decipher their origin and background. I see only what I see and think I see. Yet the meaning behind these scenes with their mythological connotations remains concealed. In some drawings yet other elements appear which then take on a life of their own, in combination – or not – with the scenes described above. A banal lemon squeezer becomes the recipient into which a stooped man and woman apparently vomit, as performers in a dark fertility rite. Sometimes the snake appears – a universal but complex and dualistic symbol- and encircles the lemon squeezer, or the same man and woman each sit enthroned on a toilet in front of a gigantic lemon squeezer.

Animals feature as well as humans – birds and apes for example – usually as spectators but sometimes as participants or as imitators of the protagonists. Occasionally the ape takes over the child’s task, or is caught in the spider web formed by the excrement between the woman’s legs. Does the ape here represent shamelessness and curiosity? The guileless birds observe and lend colour to the scene, but sometimes their droppings fall to the floor or the birds nestle on the woman’s breasts. In various drawings objects associated with housekeeping appear – objects such as a laundry basket, cushions, a sewingmachine, clothes hangers or knitting. Here and there carpenter’s tools are carelessly strewn around. Then again mysterious figures appear such as a man bearing a cross or a bull. The effect is disorientating: is this drama or comedy? To what extend are we supposed to take these symbolically charged subjects seriously?

In society the individual seldom goes unpunished through life. His being and his actions are judged and condemned. This is alluded to through the three judges seated behind a table. Somewhere they appear in a carnival setting, qualifying jurisdiction an questioning justice.

Several scenes unfold within walled interiors than in an undefined space. Closer inspection gives one the impression of a theatre decor or a film set. Life as a puppet theatre in which reality and fantasy are inextricable entwined and escape is impossible, because barred openings block the way to freedom. The longing to flee is present, personified for example in the depiction of a riverboat with algae hanging from its keel, and a bus, but they are merely decorative and hang neatly ans uselessly from the ceiling.

An atmosphere of irrationality and vitality dominates Pieter Slagboom’s work; it borders on the extravagant. But this spontaneous, intuitive, half conscious image making, this revelation of the dark conflicts of nature is rationalized and given form by the artist. We can echo Nietzsche and say that it is thank to the clear structure of the story that the dark underlying tragedy is made bearable. “…The lucidity of the depictions is seen as something superficial, like a veil wound around something dark; the clarity is seen as a clouding of that which it clarifies.” (6). Thus Pieter Slagboom seems to create a certain order in the problematic distinction between reality and fantasy, but this is probably just an illusion. He presents us with illusory images, like insoluble rebuses, so that we are intrigued and enter into his world but become hopelessly enmeshed in the game of impotence. It seems that we must constantly start anew in our search for meaning.

(1) Francis Smets: A van Abyssaal, De Vrouw als Kunst, De Kunst als Vrouw,

Garant, Leuven Apeldoorn, 2002, p. 38.

(2) Ibidem, p. 38.

(3) Frank Vande Veire: Als in een donkere spiegel / De kunst in de moderne filosofie, Sun, Amsterdam, 2002, p. 281.

(4) Ibidem, p. 205.

(5) Ibidem, p. 206.

(6) Ibidem, p. 125.