Vleeshal. Interview.

Solo exhibition 2019 Vleeshal

Vleeshal Art Prize 2018

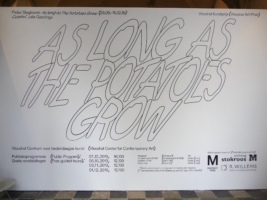

As Long As The Potatoes Grow

29.9.2019 – 15.12.2019

Vleeshal Center for Contemporary Art

Solo exhibition 2019 Vleeshal

Vleeshal Art Prize 2018

As Long As The Potatoes Grow

29.9.2019 – 15.12.2019

Vleeshal Center for Contemporary Art

As Long As The Potatoes Grow – Interview Julia and Pieter, 2021

Julia Geerlings (JG): It is exactly one year ago now that we had our first studio visit. After two full days of studio visits, I chose you as winner of the Vleeshal Kunstprijs (Art Award) 2018. We have been in close contact about your work for a year. The exhibition with the ten drawings is on now. Looking back, what has the experience of the process and our collaboration been like for you?

Pieter Slagboom (PS): It was new to me, to work so closely with a curator, with you. It was an interesting process. At a certain point, you told me I should focus on a single subject and surrender myself to the process, and not put any restrictions on myself. I had no means of escape and I was happy with that. How the drawings then came about in this installation I also experienced as collaboration. Initially we thought we would make a much larger wooden structure in which the drawings would hang. Having seen the sketches, you thought this would be too overwhelming and we went back to the basis, the drawings. Next, I designed thin wooden beams that the drawings would hang from, and then you suggested using steel.

JG: It was also a very interesting and instructive process for me. I thought it was extraordinary you were so open and saw it as a genuine collaboration. How do you usually proceed?

PS: First, I have an idea in my head for a long time. Often without realising it. By spending time in cities, for example, the ideas are freed up, so to speak. Then I begin by making small, black-and-white sketches. Usually lots of them. It’s the moment when a design is conceived. The small sketches are very close to the thoughts, in the head. They are not yet in the world. It’s why I am so attached to the small sketches. Because they actually represent the hardest moment in the creative process. They tear me open, to overstate it. They are the tools that cause me to mentally climb the slope and topple over. With the first small drawings, I begin to see the subject differently. This process, this visual psychology as I tentatively call it, continues for a few days. Eventually, an independent image comes into being. And an ambiguity. To others, the small drawings might be inaccessible. They are still too private. To make the move from the private to the worldly, the design is enlarged. I start thinking of large-scale drawings. The expansion to the physical world of color, perception and of visibility takes place on monumental linen canvases. Since I don’t want the final drawings to be enlargements of the smaller sketches, making the large-scale drawings has its own world. This is formed by means of color and scale. These ensure that revelation and perception can happen at different speeds. This tears the subject, more or less.

JG: I was immediately very impressed by your black-and-white sketches, which I find just as interesting as the finished work. How did you arrive at the color scheme for Vleeshal?

PS: I approached the work for Vleeshal differently than before. The starting point was not a series of separate drawings on separate subjects, but an installation where all works address a central theme. On the basis of conversations with you, I made a visual script and a content script with about thirty small black-and-white drawings. Many of these drawings are about the equation of life and death, as well as dying surrounded by sexual stimulation. A small study in this book shows a ballet performance made for dead spectators. This theme was not literally present in Vleeshal, but the study is in this book. For me, it was there in the background in the script. We discussed and analyzed all thirty drawings extensively. Next, I began the execution of the first large-scale drawing. To test the script thematically and technically. This was also the first drawing on canvas I had ever done. One thing I quickly felt was that this was a working method that strengthened both technique and content. Large figurations and color planes relating to the body emerged. In terms of content, too, the work began to direct itself to the viewer. So I quickly felt that with the first large drawing something started to happen that I had been looking for for a long time but had not found until then. The way the work directs itself to the viewer at first sight is crucial in terms of content and physicality. The basis at Vleeshal is that the viewer immediately experiences inescapability. And simultaneously, that this inescapability is a mystery.

In this regard, the positioning of the works in the space in relation to the viewer plays an important role, as well as the color scheme of the drawings. In composing the drawings, I look, for example, at what the height of the head of the viewer will be in Vleeshal. And also what the height of the viewer’s stomach will be. And next, I consider what I want to have happen in the drawings at those specific heights of head and stomach. Consequently, for the viewer a physical moment will creep imperceptibly into the installation, between him or her and certain figurations in the works. In the case of the artwork Pushing Against Dying Head, for example, the height of the viewer’s head is where the dying head of the protagonist is jammed between vagina and penis. The structure of the installation is, then, such that things do not happen by chance in a certain place in the drawing, but are consciously coupled with space and body in Vleeshal. Color has a dominant effect in the revelation of the installation. The aim is for color to disengage the subject. So color here functions in a slightly unusual but important way. Form and content are revealed at different speeds in the installation. Its large format allowed me to design fast and slow areas, as I call them myself. Even stationary areas. This is brought about by chromatic and monochromatic areas. In these I find the viscosity and the problematic I am looking for. The one part of the subject reveals itself very quickly, then, and the other, much more slowly. Sometimes not until a day later. Or when people return to the exhibition to see it for the second time.

The execution of this project is labor-intensive. Working on canvas is new to me. Due to the expansion of scale, the pencil lines are very thin, relatively. At the same time, I want powerful color for this large scale. So I apply several layers of color. Six thousand pencils are needed to build up the color. To create the lines I want, I have to press the pencil hard into the canvas. Since the lines are long, the line is also a walk. Sometimes up and down stairs. This is a physically intensive process. It is important that a 300 x 500 cm canvas consists of a single piece and is not a composite of smaller pieces. In the end, this process results in a color intensity that relates to perception and observation time in a new way.

JG: In terms of content, the viewer also perceives the work in a different way as a result of the expansion of scale.

PS: Correct. The expansion in scale results, in its turn, in a moment of time extension in the works. The time of decoding is prolonged. A moment in time is created between the viewer and the work in which the movement of the viewer plays a role. The color scheme, then, is not based on compressing the image but sooner on disassembling it, and dispersing it through the space. So the ten drawings in Vleeshal blend together. One can continue itself in another. They form a unity. The viewer consequently walks through this unity. The positioning of the works in relation to each other is partly based on this. The revelation of this unity is consciously shaped by means of a labyrinth. A maze. A place of wandering. This labyrinth creates large and small spaces within Vleeshal. The principle here is that the size of a space reinforces the content of a work. Differences of scale emerge. The space is molded. The viewer senses this. In this way, the color scheme is closely interwoven with the labyrinth in Vleeshal and with the way perception is guided in the space. With revelation in varying tempos and with the tearing of the subject. For the first time, figuration, movement, architecture, viewer and color interlock.

JG: Walking or wandering is important for your practice and your thinking in general. This was then also the source of the concept for guiding the viewer through a kind of labyrinth in the exhibition, past the drawings. The size of the drawings plays an important role in this. Could you tell us about this?

PS: In recent years, my drawings have become increasingly larger. I drew on a large scale before, but that was directly on the wall. This is the first time that I have worked on a large scale on prepared linen canvas and shown so many drawings at once. In the Vleeshal project, I emphatically place my work in the contemporary world by means of an expansion of scale. I place the themes among living people. I confront the living individual. I want to keep the viewer from looking away. For the spatial organisation in Vleeshal, I have used medieval Middelburg’s map of narrow streets as the basic principle. It is claustrophobic here and there. Wide streets alternate with narrow ones. Large squares, with small ones. I wanted the viewer in Vleeshal to move between the works from narrow corridors to larger open spaces. Sometimes you are very close to a drawing and elsewhere there is more room to view the drawing.

I call the floor plan a psychogram. Influenced by their color and the composition in the space, the drawings are not ‘suddenly’ and not ‘frontally’ present. They slowly take shape on the retina. The longer the viewer walks through the space, the clearer the form and content become for him. The revelation of the theme and iconography is a spatial process. At one drawing, the viewer is pressed close to the work, while at another drawing, he can take lots of distance. The space rhythmically contracts and expands. Like the peristaltic movement in the body. The method of perception therefore varies from drawing to drawing. The human figures in the works are on a larger scale than that of the viewer. Intimacy is magnified and redefined. The installation is designed in such a way that rituals constantly surround the viewer. He cannot look away or walk away from them.

JG: You certainly cannot escape. The content of the drawings is confrontational, too, and could be perceived as provocative. Can you tell us about the themes of the drawings?

PS: I don’t consider them provocative myself. In any case, I haven’t drawn them to be provocative. I think it is the combination of sexuality and death that makes people uneasy. To me, these subjects are actually closely related. How we look at that varies from culture to culture. In Christian, northern European culture we have difficulty with expressions concerning sexuality and death. There are many taboos surrounding these issues. I hope the viewer will take the time to look carefully at the drawings. There is, in fact, more to them than the clear, explicit level. There are several images to be found in one image.

JG: How do you view the relationship between men and women? In your work, women seem dominant and men, passive. Where does that come from?

PS: In my view, the individual is most important. It does not work to consider men and women as groups. No one is a group. Since you ask, however, I will try to say something about it. I will start by saying that I do not understand men and women exist. I sometimes consider my work to be sexuality in reverse. I cannot (yet) explain this further. But it is a compelling feeling. As I see it in history, women are superior to men. She is creative, while he is destructive. Having said this, nuance immediately follows, of course. Because there are men who create (art), too. What has always amazed me is that feminists undervalue the role of women in history. And marginalise it. In my view, they play the lead. Looking at cultural history, woman has a central role. Although it is different from than the role of the man, it is extraordinarily powerful. So in my view, feminism is also an underappreciation of the significance of women throughout history. Of course, she gives shape to her significance in the world in her own distinctive way and, obviously, not in a masculine way. Subtly and inconspicuously, she directs the entire culture. The feminine and the masculine, in my view of history, are both manifest. This broad and general perspective can also be seen on a smaller scale, that is, in the relationship between man and woman: as partners. Sometimes I think it would be better to subdivide the world into testosterone (present in both men and women) and estrogen (present in both men and women). Testosterone as war. And estrogen as creativity. The relationship between man and woman is also tragic. I felt this vividly as a child. With my head pressed to the floor, playing with miniature crane trucks, I would look up and see the world of big people through the arms of the cranes. Up there, it was thick with cigarette smoke. Like clouds in the sky. Adults in these clouds of smoke were as large as gods. That was where conflicts were fought out. It was also where my mother and father were driven apart. As a child, it makes you feel like an unsuccessful conception. A failed coitus. It frustrates a child.

JG: Interesting view. To me, feminism is especially the emancipation of the woman and a critique of the unequal (power) relations between men and women. For that reason, I think the idea of the subdividing the world into testosterone and estrogen is very appealing. What is the role of animals in this within your work?

PS: Animals symbolise the human problem. The animal gets something moving that is blocked in the human. I see the animal as a higher form of life than the human. The hopelessness of the human is, however, what makes him appealing to me. As a basis for creativity. The animal has a different spatial floor plan than the human. For humans the eye determines direction; for animals, the nose. Animals also represent the unconscious. The mysterious. Our pre-human existence. Instinct. The wisdom of the animal in comparison to the ignorance, shortsightedness and greed of the human. The animal to me is a space very nearby, but at the same time, utterly foreign. The status of the animal in my work is that it is elemental. This happens in a society where this is not the case.

JG: In that sense, I also find the title of the exhibition, ‘As Long As The Potatoes Grow’, revealing. This is how I interpret it. We are all part of the cycle: being born, living and dying. We can pretend to be exceptional, but ultimately we are all part of nature and a product of biological urges none of us can escape. In the drawings, I see recurring rituals and symbols. Could you elaborate on that?

PS: I find it difficult to explain the drawings completely. I am afraid that they would become flat and one dimensional. I would prefer to leave room for interpretation and sometimes I also don’t know myself why I have drawn something a certain way. However, the way I draw a subject, technically, is a way for me to express how I relate to the relevant subject. Technique becomes symbolic for the subject matter. Intense scenes are calmly and precisely drawn. An often-recurring motif in my work is, for example, a sniffing dog. I’m interested in animal behavior and the fact that culture has not been imposed on them. They are free and have no taboos. Dogs look with their noses. They perceive the world by means of scents. Looking at art ought to happen via the belly and not the eyes. Feet and the soles of feet are also recurring symbols. A bare foot touching the ground can literally ’ground’ itself. Perhaps the works raise more questions than answers. To me, drawing is a means of survival and would naturally hold personal elements. To me, other artists who are obsessively concerned with psychological oppression in their work are Jockum Nordström, Luis Buñuel and Diane Arbus.

JG: Could you try to define the biographical aspect in your work? Without looking too hard for Freudian significance behind it.

PS: A near-death experience has shaped me and influenced me in my work. When I was eight years old, I fell into the water in a marina. I can still remember well that I started consciously to take my leave, from my family and from my electric train. Fortunately, an attentive Belgian yachtsman rescued me in the nick of time. The birth of my children also shaped me, as well as my unconventional upbringing. I grew up in a family where feminism and free love were important. You take that with you as a child. Still, I also see the universal and social sides in my work. What you could also take as a biographical aspect is that I learned from childhood on to look precisely at the contemporary world. I observe mankind in all its illogicality.